Vous pouvez trouver la version française here

In order to better understand the challenges of the organic waste sector, Future of Waste conducted an exploratory phase over several months during which we met with stakeholders, in particular bio-waste producers and operators. Interviews, citizens’ meetups, literature review… From those rich exchanges, we have drawn several challenges and topics for reflexion, summarized below, and which have helped us to define the scope of our 2019 campaign, focused on food waste.

#1 context of biowaste sector

- ⅓ of world food production is thrown away, and this figure is likely to increase according to several forecasts.

- 2,600,000 people in France lives from food aid distributed by major humanitarian associations, according to the French Federation of Food Banks.

- ⅓ of European household waste bins are made up of bio-waste.

- 40% of French soils are estimated to be deficient in organic matters.

You may be wondering, what is organic waste?

Fermentable waste, bio-waste, catering waste or kitchen and food waste … many terms are used and complexify the understanding of the sector. Those labels are not steady, and overlap varying perimeters, more or less exhaustive, depending on actors or countries. In France, only the word “biowaste” has a definitive definition, specified by the Environment Code.

Organic waste, or fermentable waste, are waste of living origin – vegetable, animal, human – and therefore biodegradable.

Within organic waste, bio-waste consists of food waste and other natural biodegradable waste. They are defined as “Any non-hazardous biodegradable waste from parks or gardens, any non-hazardous food or cooking waste, particularly from households, restaurants, caterers or retailers, and any comparable waste from food production or processing units.” (Environmental Code, Article R. 541-8, and Article 543-227)

Finally, among bio-waste, food waste is directly related to the use, processing and production of human nourishment.

For this 2019 campaign, we have chosen to focus primarily on food waste, because its collection and recovery still remains fledging compared to other flows, such as green waste. In a similar way, we will mostly overlook the challenges of the agricultural and agri-food sector, because due to economic concerns, they have largely implemented recovery loops on the remaining ‘substances’ from their production processes (via reuse, animal feed, methanisation…). In this sense, these substances are labeled as co-products or by-products, and are not even considered as waste.

Why get involved on organic waste ?

The prevention and recovery of organic waste has many advantages, including economic ones =>

143 billion euros each year, or the equivalent losses related to food waste in Europe, according to a report from the European Parliament.

88 million euros, or the biogas sales achieved in France in 2015, according to a report by ADEME

- 2.5 billion euros of potential savings by avoiding the use of synthetic fertilizers on 5% of French agricultural land according to FNADE’s estimates.

and environmental issues, through preservation of =>

- natural resources used for food production, by reducing food waste and improving soil productivity,

- biodiversity, through natural fertilizers that are less aggressive than chemical ones,

- climate, thanks to the generation of green energy and the reduction of greenhouse gas emissions that emanate during various life-cycle stages of a food product.

At the crossroad of various stakes, bowaste are regulated by environmental, farming, energy and health policies. With the objective to reduce the environmental and social impact of biowaste, the regulations are evolving rapidly. In Europe, the Circular Economy Package adopted by the European institutions is accelerating a still fledging management.

Hierarchy of bio-waste management methods Source: ADEME ConcerTo 2019

In France, the majority of bio-waste is still incinerated or sent to landfill, while many recovery methods exist

The recovery of bio-waste is conditioned by its sorting and separate collection. The generalization of source separation is planned by 2023 in France, for all producers of bio-waste, both companies and individuals. Currently, most household biowaste ends up in residual household waste, the number of local authorities having adopted separate collection being still quite limited. Concerning private actors, those producing more than 10 tonnes of bio-waste per year have the obligation to sort at source since 2016 (Decree 12 July 2011). However, many professionals are not aware of their obligations, because the obligation is defined based on the measure of an annual tonnage, while those actors rarely weigh their waste. There are diverging opinions on the means to be put in place to enforce the laws, in particular through awareness-raising, the application of financial penalties, or the clarification of certain laws.

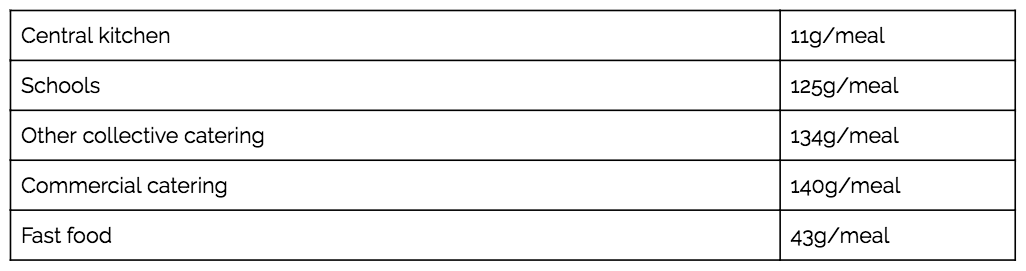

The GNR (National group for catering) in partnership with ADEME, established in 2011 ratios of bio-waste production ratios in order to help stakeholders to better understand their bio-waste production.

Starting from a simple observation – there is a large quantity of biowaste produced, and technical solutions relating to its treatment exist – how can we explain, and resolve, the lack of development of the sector ?

We have identified 3 essential challenges for the sector, and on which Future of Waste could contribute to their resolution. The complexity and the limitation of this exercise lie however, in the diversity of the actors concerned, in particular households/economic actors, rural/urban communities… which do not have the same constraints (regulations, flows,…).

Nevertheless, the bio-waste sector is inexorably integrated into a territory, and this requires coordination inbetween the actors and their flows, and inbetween the links of the management chain – sorting/collection/treatment/recovery. Thus, the first challenge we have identified to catalyse Future of Waste’s efforts relates to the integration and interconnection of actors and flows within the supply chain, which requests to find the appropriate management scale.

Facing the burst of the bio-waste sector, one of the major risks would be the dispersion of costs and values, which could weaken the profitability of all actors. In order to support the sustainable development of the sector, the second challenge we identified below related to the economic models of bio-waste management.

As the bio-waste sector is relatively young in France, it naturally faces a lack of acculturation, fed by ignorance and perceptions of dirt interlinked to its fermenting feature. Future of Waste will act to contribute to this last challenge, in a process of awareness raising, clarification of the subject, and dialogue between the actors, which are at the heart of its core missions.

1. Find the appropriate scale

The fragmentation of the bio-waste sector emerged as a major feature in our interviews. There are many producers of bio-waste, with a variety of of quantity, flow and location. For example, agri-food producers have integrated this management more into their value chain than restaurateurs or mini-markets, whose flow are diffuse and still complex to estimate.

Data ADEME 2013

In parallel with this market fragmentation, the evolution of regulations has allow the development of many solutions (composting, vermicomposting, in situ methanisation, silo composting, entomoculture, eco-digester, food waste paint, bio-tank, etc.), particularly by social and environmental entrepreneurs (see our database). We have found that these solutions are often very localized, dedicated to a specific stream or even a specific processing cycle, raising issues of structuring the supply chain and reproducing solutions.

![]()

Focus : the LowTechLab shares frugal innovation knowledge, tools and methodologies that can be replicated around the world. In 20 minutes, you can create your own personal vermicomposter, for example!

Faced with this fragmentation of the sector, there is no single solution, each solution must answer the constraints of the territory and bio-waste producers: What volume, distance, and frequency of the waste deposits? What types of flows and quality? What changes over time? what infrastructures are already in place?… Finding and choosing an appropriate solution remains complex for bio-waste producers, which requires greater visibility and adaptability of the available solutions.

Unlike recyclable waste, for which individuals and professionals clearly identify the recovery channels, biowaste solutions are plural and not yet widespread. For example, in France only 5.8% of the population has access to separate collection of bio-waste.

This figure illustrates in itself the dormant stage of bio-waste. The small quantity collected, from households, but also from the private sector, disrupts the management of an already extremely diffuse deposit that requires massification and gridwork efforts. The lack of regularity and visibility of deposits naturally influences public investment.

At the territorial level, bio-waste management requires integrated governance, in order to avoid conflicts of supply or uses, and to rationalize management methods. To create a territorial coherence, synergies are needed in between household and industrial bio-waste, and in between sectors. In France, for example, bio-waste is covered by several territorial planning tools, such as PLPDMA, PCAET, PRPGD, SRCAE, PAT…

While the complementarity of prevention solutions (awareness, donation, sales of unsold products, etc.), proximity solutions (mulching, neighbourhood composting, autonomous composting, etc.) and industrial solutions (composting plant, mechanical-biological treatment, etc.) is obvious, effective coordination still needs to be improved in order to encourage bio-waste producers to take action and make the sector more sustainable.

2. Rethinking economic models

During our interview phase, the first obstacle mentioned to wide spreading bio-waste prevention and recovery has been economic. Two main factors support this argument: the lack of capital for investments and the unwillingness to increase waste management expenses.

In France, the food waste prevention sector has flourished thanks to recent regulations with economic incentives, in particular the 2016 law tackling food waste. According to several actors, more than the punitive aspects (3750 euros fine per offence), it’s the incentive aspect that has accelerated behavioural changes, in particular through the tax exemption of food donations (Article 238 of the General Tax Code). Concerning the obligation to sort at source bio-waste, the Environmental Code provides criminal sanctions in the event of non-compliance (fine of 75,000€ and two years’ imprisonment, Article L. 541-46, point 8), and discussions are still ongoing on the incentive side (state aid, reduction in VAT…).

![]()

Focus : ADEME’s Waste Fund With an annual budget of 163 million € (2018), the Waste Fund aims to support local actors who carry out prevention and recovery operations, namely local authorities, companies and the intermediary organisations that support them (associations, operators, etc.).

Despite the legal obligations to sort bio-waste at source, both public and private actors can often be reluctant to add another sorting line (and its associated costs):

- French local authorities are required to sort at source by 2023 (Circular economy package of the European institutions). According to the National Waste Management Service Cost Reference, bio-waste represents 10% of the households waste management costs. There are however significant disparities, ranging from 3 to 38%

- Since 2016, private actors have been required to sort and recycle their bio-waste, if they produce more than 10 tonnes per year (Directive 2008/98/EC). Costs vary according to the collection and processing methods.

Several actors noted that there were misunderstandings regarding the associated economic costs. Some actors overestimate prices that they imagine unaffordable, while others have the illusion of a free, or even remunerative service, thanks to the creation of new resources (fertilizers, energy…). Thus, rethinking the economic costs of bio-waste involves clarifying and deconstructing misconceptions, but also reinventing the services to ensure an “accessible” cost.

Beyond costs, these reflections concern mainly the viability of economic models, with the sector still often facing competition from cheaper management methods, such as landfilling or incineration. The sector is gradually structuring, with several measures and innovations aimed at transforming the existing economic models:

The first area of improvement consist in influencing the financial balance of bio-waste management services. In order to increase and secure revenues, several outlets are being developed, in particular energy production, with biogas (whose price is becoming more institutionalized) and cogeneration. Since July 1, 2017, in addition to sales for domestic animals, insects fed with bio-waste can be used for aquaculture, and discussions are ongoing for farm animals. Compost (with NF U 44-051 standard), can be sold to private individuals, farmers… in bulk (~20 €/t) or in bags (~160 €/t). Platforms are emerging to connect producers and consumers of bio-waste derivatives.

The operating costs of bio-waste management are often compounded by the under capacity of the territorial grid. The evolution of incoming flows in quantity and quality, via the generalization of biowaste sorting, would increase their profitability of biowaste sites. At the same time, rethinking logistics methods remains strategic, given the cost of collection and the diffuse nature of the deposits. Soft mobility and the digitalisation of urban logistics offering new alternatives.

A second axis of evolution of the business model consists in expanding the scope of the service. Reduction of food waste and distinct sorting of bio-waste systematically leads to a decrease in residual household waste for households (45% on average according to ADEME), and the private sector. In addition, it also affect and leverage the sorting of the remaining recyclable waste. The reduction in the volume of residual waste thus makes it possible to reduce the frequency of their collection, and ultimately their cost. In this perspective, new equations could be imagined. Incentive pricing, for example, introduces a billing system that reflects these changes, with the price being proportional to the service consumed.

Finally, a third area of work emerged from our discussions, taking into account the indirect effects of bio-waste management. For many stakeholders, the cost of waste management is understood as the price recorded in the accounts register, invoiced by service providers. In reality, it is also possible to include the cost of internal management such as handling or storage.

Anti-gaspi start-ups such as Phoenix and Too Good to Go tackle some of the “hidden costs” of bio-waste production, namely the purchase of raw materials and consumables, which are usually attributed to the product costs, not to the waste costs. In addition to contributing to the reduction of food waste, stores and restaurants make profits from the sale of otherwise discarded products at reduced prices.

The management of bio-waste also brings positive image and trust for consumers. For example, in canteens, preventing the creation of bio-waste can consist in adapting dishes to the tastes of the guests. Adopting an environmental approach can also be an axis of differentiation in terms of image with (potential) customers. The gradual emergence of labels or a communication campaign could facilitate the visibility of these approaches.

3. Improve the understanding and acceptability of bio-waste

Recent changes in legislation have highlighted the disparity in knowledge of many stakeholders about their bio-waste.

Although stimulating fundamental changes, laws at European and national level are evolving faster than attitudes and practices. The management of bio-waste remains a topic that still needs to be democratized. In fact, many waste producers are not yet aware of their sorting and recovery obligations. Especially when they are concerned on the basis of an annual tonnage, whereas they rarely measure the weight of their waste. Opinions differ on how to change this, in particular through awareness-raising, strict application of the law and financial penalties, further clarification of laws…

More controversial, the acceptability of bio-waste divides. The image of bio-waste and its management keeps an idea of impurity, dirt, linked to the fermentable nature of this waste. The risks of bad smells, pests (midges, rats…), lead to reluctance on the part of public actors, as well as guards and citizens. In the food industry, the focus is on health and sanitation, the lack of space and time wrongly create a barriers to improve bio-waste management.

![]()

Focus: In order to reassure and convince local authorities of the importance of recycling bio-waste, the Compost Plus Network organises exchanges between peers with elected officials, via site visits and meetings with other local authorities that have adopted these practices.

Habits, cultural (“habitus”) or repetitive, also play a strong role, sometimes accelerating or hindering the reduction and recovery of bio-waste. In restaurants, for example, the quantities of food served on the plates are a guarantee of the generosity and satiety of the guests, but also a source of food leftovers. The implementation of sorting also entails an adaptation of the operating methods and working habits of staff and users.

Thus, in order to avoid reluctance or rejection of new practices for the reduction and recovery of bio-waste, several areas of work are emerging.

The ways of approaching users is naturally central, especially in an information society saturated by solicitations and awareness-raising campaigsn. According to the actors, the message should naturally adaptsto each individual concerns: national objectives for reducing residual household waste, regulatory obligation, control of waste budgets, contribution to the Sustainable Development goals, soil productivity through compost, attracting new customers, preservation of the environment, social contributions of donations, boosting local economic development, … and so on.

The management of bio-waste offers the particularity of making its impact easily visible. Unlike other waste streams, bio-waste will lose value with transport, and thus encourage short circuits of recovery. The benefits of compost or biogas are directly visible by the waste producers, and would help to bring more value (and confidence) to the sorting process. Similarly, the link between bio-waste and return to land and food is still not very visible.

If the speech is important, so are the people who relay it. Understanding the problems and responding to questions and concerns require appropriate and often local contacts.

Focus : The Paris City Hall has set up the sorting at source of bio-waste in the 2nd and 12th arrondissement of the capital. In order to support this new gesture of sorting citizens, the local authority has sent many bio-waste referents, i.e. about a hundred people recruited in civic service or agents from the cleaning section of the city of Paris as well as the Syctom. Through door-to-door meetings, they raised awareness, informed and distributed “little bins” to the citizens of the two boroughs.

Similarly, places of awareness are diversifying:

Both prevention and management of biowaste requires an active implication of waste producers. Local actions allow to develop of the social connection and create space for more socialization, encouraging individuals to engage on the long term

![]()

Focus: OrgaNeo offers trainings and help local authorities in their composting projects and fighting food waste. They encourage a variety of commitment, through collective composting or using games such as compost challenge.

#3 Tomorrow, what will be the Organic Waste campaign?

In 2019, Future of Waste launches the new campaign “Organic Waste” to work on biowaste and the challenges shared in this article. It is a multi-stakeholder campaign in Europe to share, gather and develop local solutions. We wish to work with citizens, experts, circular entrepreneurs, and waste producers to identify collectively the solutions to reduce, collect, compost and valorize the organic waste.

Our campaign will have 3 main goals:

1. Develop multi-stakeholders collaboration and entrepreneurs projects.

To work toward structuring the sector and helping new solutions to emerge, we will:

- Develop multi-stakeholders collaboration: through workshops and other meetings, we wish to allow exchanges and co-build projects which answer local organic waste challenges

- Support the scale of entrepreneurs through a 2-day bootcamp with training and experiences sharing of experts, mentors and entrepreneurs.

2. Share existing and effective solutions

In order to encourage the change of behavior for bio waste producers, we want to clarify and give visibility to existing solutions, with a particular focus on economic models. To do this, we will rely on 3 tools:

3. Gather various stakeholders and perspectives around concrete projects

In order to raise awareness and share the concrete impact of the initiatives with the citizens, we will organize events, workshops and local tours. The local tour goal is to gather during 2-3 hours, a dozen citizens and professionals, curious to meet local initiatives, to know the means of action and their impact.

Would you like to join us on this campaign?

- Attend or host an organic waste event

- Join our online community

- Contribute and discover our organic waste database

- Share this article and contact us at futureofwaste@makesense.org to collaborate.

- Discover our bibliography on organic waste

Organic Waste is a Future of waste campaign launched by makesense and SUEZ, aiming to find, support and promote circular solution.

Main author of this article:

-

-

- We would like to thank the experts and professionals of the sector who have given us time for these interviews, to share their points of view and help us understand the issues and design this new campaign:

- Social and Environmental Entrepreneurs

- Paul Adrien, Menez co-fondateur Zéro Gachis

- Camille Colbus, directrice des opérations Too Good to Go

- Clara Duchalet, fondatrice Vepluche

- Alan Le Jeloux, CEO Organeo

- Margaux Moi, Chargée de projet compostage Upcycle

- Jean Moreau, Co- fondateur Phenix,

- Jerôme Perrin, president Love your Waste

SUEZ

- Pierre Achard, Market Director

- Jean-Baptiste Décultot, Directeur du Développement, et Yann Priou, responsable innovation smart et digital, at Suez Organique

- Sandrine Villedieu, responsable marketing biodéchet

Institutions, companies and networks

- Marie Boursier, chargée de mission déchets et territoires ADEME

- Thomas Colin, animateur du réseaux Compost plus

- Guénolé Conrad, coordinateur technique Low tech Lab

- Mathilde Gautier, chef de projet cellule innovation Biocoop

- Thomas Haden, Ingénieur de recherche en agriculture urbaine Agro Paris Tech

- Patrice Poignard et Eric Poisson, Direction de la Propreté et de l’Eau mairie de Paris

- and our Impact Board members, including : Pascale Alexandre, Antoine Delaunay Belleville, Sophie Florin, Laurent Gerbet, Nathalie Héry, Joannie Leclerc, Alizée Lozac’hmeur, Nathalie Parineau, Catherine Pradels,

-

Enter your address to have adapted content

Enter your address to have adapted content

Find us